There’s an astonishing moment in Bad River, director Mary Mazzio’s riveting documentary film about the fight between Enbridge and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, that features Enbridge’s Chief Communications Officer Mike Fernandez. While criticizing the Bad River Band’s perfectly legitimate demand to have Line 5 removed from their reservation, Fernandez has the temerity to put words in the mouths of the tribe. “You have a tribal community,” Fernandez ventriloquizes, “saying, ‘we don’t care about the millions of people that are dependent upon the 540,000 barrels of oil that are going through that pipeline on a daily basis.’”

It would take more than a single post to unpack all that’s wrong with such an outlandish speech act, from the appalling erasure involved in trying to speak for the Band in the first place to the laughably hyperbolic claim that “millions” of people are dependent upon Line 5 oil. But what is most extraordinary about Fernandez’s statement is its victim blaming. This is, of course, a 500-year-old rhetorical tactic employed by white settlers in North America to exculpate themselves for centuries of exploitation, dispossession, displacement, and genocide. Just as Indigenous populations, to recall the language of the nineteenth century, must “vanish” and become “extinct” to make way for so-called civilization, so does Fernandez’s logic suggest that the Bad River Band should sacrifice their sense of place, their relations to the water and land, and their values so that millions of other people can continue to consume (and in some cases profit from) massive amounts of petroleum.

I thought of this moment in the film upon hearing the news last week that six Michigan tribes have withdrawn from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Line 5 tunnel review process. The tribes’ bold decision to walk away from those discussions comes in response to the likely fast-tracking of the required Army Corps tunnel permit under the Trump administration’s phony “energy emergency” order. Like Fernandez’s statement, these moves by the White House and the Army Corps are part of a very long and ongoing historical process. As Whitney Gravelle, President of the Bay Mills Indian Community, put it, “once again, the federal government has cast us aside and failed us.”

In other words, when it comes to the treatment of Indigenous peoples, not much has changed over the past couple of hundred years. In fact, if 2025 is any measure, one might even think that things have gotten worse.

Let me illustrate these two points with a story. You might find it familiar.

A hundred and fifty years ago, before Big Oil, there was Big Timber. All along the upper Great Lakes region, lumber barons acquired vast tracts of old-growth forests from which they harvested and milled trees, especially valuable white and red pine, which grew in abundance across central and northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Nineteenth-century logging was not unlike the oil booms of the twentieth century; lumbermen extracted timber recklessly, as if it were an endless resource, processing millions of board feet per year and making fortunes from the wanton destruction of wilderness ecosystems. By 1900, for example, more than eighty-five percent of northern Wisconsin’s old-growth pines had been harvested.

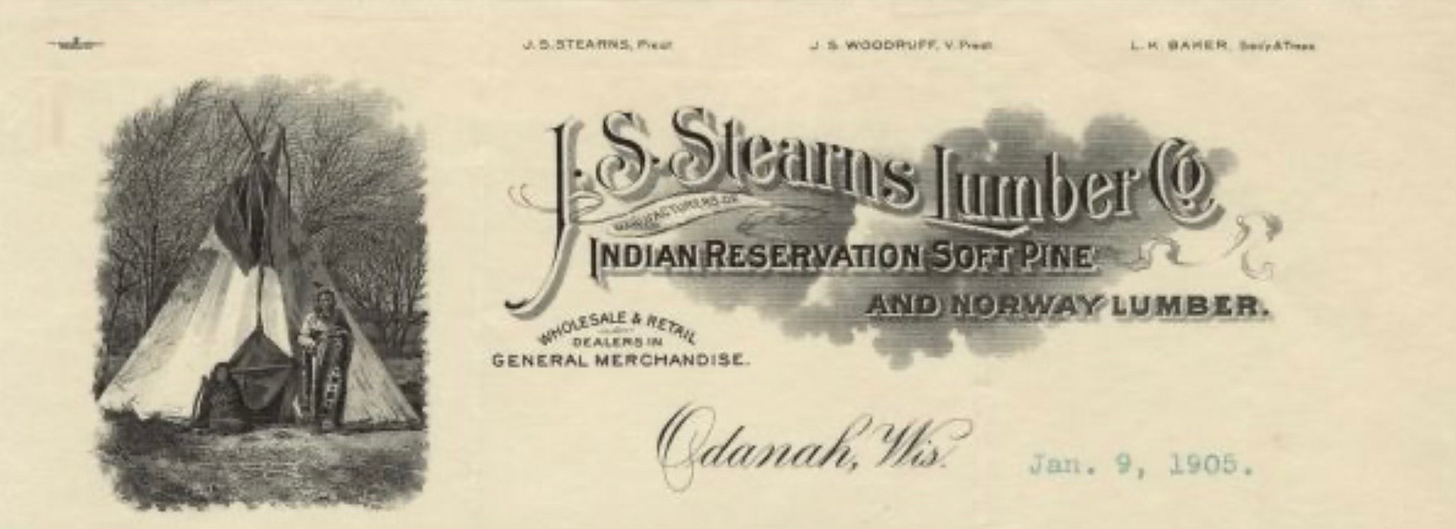

Since about the 1840s, the federal government, through the Bureau of Indian Affairs, had encouraged logging enterprises on reservation lands, including those established by the two La Pointe Treaties (1842 and 1854), such as the Bad River Reservation (in the early days called the La Pointe Reservation). The state of Wisconsin, mistakenly believing it owned the wilderness tracts there, sold thousands of acres of that land, much of which was bought up by firms like the Ashland Boom and Canal Company, which constructed booms in the Kagagon and Bad River sloughs to gather and transport timber for market, and the Stearns Lumber Company, founded by an entrepreneur from Ludington, Michigan named Justus Stearns. Stearns Lumber cleared the Bad River reservation of its primary stands of pine, hemlock, fir, and cedar in just twenty-five years.

If you’ve seen the film, you know that the Bad River Band, historically, does not fuck around. And indeed, the tribe fought against timber exploitation on the reservation for decades. In 1918, they even won a U.S. Supreme Court case that ruled that lands the state sold to the Stearns Lumber Company belonged to the tribe. A few years later, in 1923, the tribe filed a lawsuit against Stearns Lumber, Ashland Boom and Canal, and the state of Wisconsin, claiming years of trespass and seeking damages of more than a million dollars.

As you’ve probably noticed, the logging trespass on the Bad River Reservation of the 1920s bears an eerie resemblance to the pipeline trespass on the Bad River Reservation of the 2020s. Other than the resource—timber then, oil today—not much has changed in a hundred years.

There is one significant difference, however. In the 1920s, the Band filed its suit just after the state of Wisconsin, by an act of the legislature, admitted its liability in the matter and affirmed the trespass of the logging companies. That’s right, the Wisconsin legislature took the side of the Bad River tribe. In fact, two years later in 1925— almost exactly 100 years ago to this day— the Wisconsin House and Senate passed a joint resolution authorizing the state to join the Bad River Band as a party in the lawsuit against the timber companies. Newspaper reports lauded the action as an effort by the state “to right… a colossal wrong.”

Where is this kind of legislative allyship, this sort of frank acknowledgement of historical injustice today? Wisconsin’s legislature certainly hasn’t affirmed Enbridge’s trespass, joined the Band’s suit, or even so much as passed a non-binding resolution of support for the tribe. In fact, the best Wisconsin’s elected officials have been able to muster this century is a draconian bill that punishes pipeline protestors. In Michigan, matters are no better. Instead of introducing legislation to repeal the Snyder-approved tunnel agreement or passing a resolution affirming the Treaty rights of Michigan tribes, the Michigan House passed a resolution in 2022 calling for an end to the Attorney General’s effort to Shut Down Line 5. In 2023, a group of Republican senators called on the Army Corps to expedite the tunnel permit. Meanwhile, Democrats, in complete control of the state government that same year, stood idly by like spectators.

Personally, I don’t expect much from extractive capitalists, from the Justus Stearnses and Mike Fernndezes of the world. But I’m old-fashioned enough to still expect something from my elected officials; in our present system of government, we have to, perhaps now more than ever. Yet here we are, represented by legislative bodies that lack even the courage and moral vision of legislators a full century ago. This ain’t progress, folks.

Bad River is available to watch on Peacock.

Keep calling out the injustices, Jeffrey! We can each keep taking what steps we can to right this insufferable wrong. For those new to this travesty, check out Oil and Water Don't Mix or For Love of Water for more information and to join the movement toward resolution of this mess.

Oil is the devil's blood. Pollution=Corruption=Ignorance.