Enough of this tunnel talk. The last couple of weeks, in response to court proceedings, I’ve written here about Enbridge’s preposterous tunnel scheme. Last week, for example, I underscored how taking the tunnel seriously requires a kind of intellectual partitioning that disconnects the Straits of Mackinac segment from the rest of Line 5 and, in doing so, deliberately obscures the bigger (climate) picture of fossil fuel infrastructure investment.

Sometimes, I worry that the intense focus on Line 5 at the Straits, even among those of us working toward the pipeline’s decommissioning, risks duplicating or reinforcing that same kind of partitioned thinking. Don’t get me wrong; I treasure the Great Lakes as much as anyone, and the danger at the Straits is unique and worthy of our attention and action. But so, too, are the other 641 miles of Line 5. These sites may lack the charisma of the Great Lakes, but they’re still important.

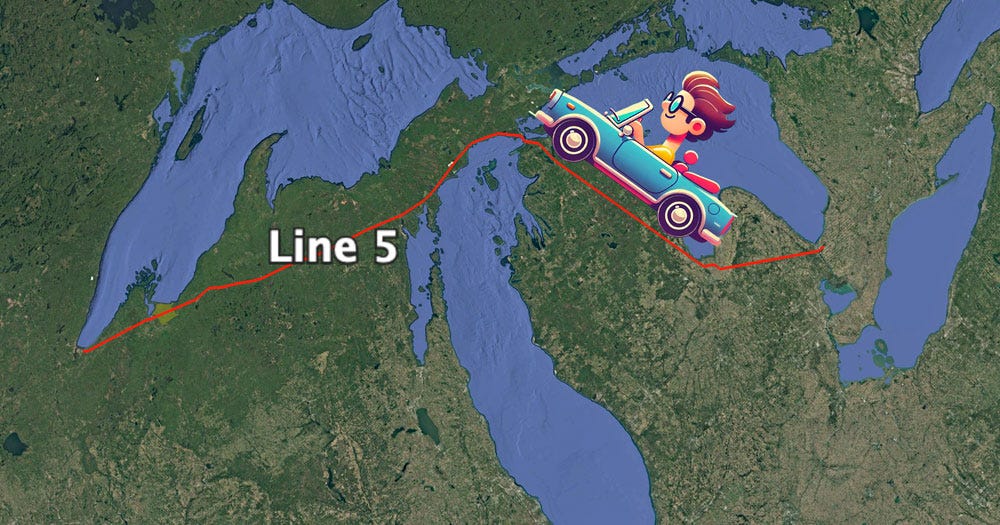

So, in the coming weeks here at The Current, I plan to devote some space to the rest of Line 5. It crosses hundreds of streams and rivers, traverses acres of wetlands and numerous watersheds, cuts through miles of forests, fields, and farms; it even crosses city streets. To see all of this, last fall, over the course of a week, I drove the entire length of Line 5 from Sarnia, Ontario to Superior, Wisconsin, stopping frequently to witness and observe. These other sites, that trip taught me, have their own compelling stories to tell.

Consider Gogebic County at the westernmost end of the Upper Peninsula. It’s home to the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, so named for the lake the Anishinaabe call Gete-gitigaani-zaaga'igan. The Band has lived on the Lac Vieux Desert Reservation, established by the La Pointe Treaty of 1854, for more than one hundred and fifty years. Gogebic County is also home to more than a thousand rivers and streams, a number of which feed Lake Gogebic, the largest lake in the UP. The Ottawa National Forest, established in 1931, also covers most of Gogebic County. The forest features rolling hills, waterfalls, and acres of old-growth maple, white pine, and eastern hemlock. Even in November, when I took my drive, the grasses and foliage maintained their rich bronze, gold, and red colors. The landscape was breathtaking.

I reached Gogebic County on the fourth day of my trip. By then, I’d driven along some 350 miles of U.S. Route 2. On that kind of journey, signs of Enbridge and its pipeline remain hidden—only a series of carefully mapped out diversions from that main thoroughfare revealed the orange pipeline markers and swaths of denuded right-of-way slicing through otherwise dense wilderness that I wanted to see. It was a little startling, therefore, while passing along a lonely stretch of Route 2 just south of Lake Gogebic, to come across one of those familiar Adopt-a-Highway signs reading: “Next Two Miles, Enbridge Energy Partners, L.P.”

Enbrige Adopt-a-Highway sign, Gogebic County, MI

Of the hundreds of miles along the highway, I wondered, why here? Why this spot?

There’s no way to know, of course, why Enbridge chose to adopt that particular stretch, but thinking about the history of the pipeline, it’s hard not to see the sign as something like a marker of guilt, a silent admission of culpability.

It turns out Gogebic County happens to be the site of the first Line 5 spill I’ve been able to document, way back in 1959. I have yet to identify the site of that particular spill with precision, but I do know that in 1976, another rupture from Line 5 happened just about a quarter mile from Enbridge’s adopted highway sign, right near Tenderfoot Creek. That incident spilled 210,000 gallons of oil and injured two people. Eight years earlier in 1968, just about a mile from the creek and right in the middle of Enbridge’s adopted stretch, Line 5 had spilled 96,000 gallons of oil into a wetland. And the same year, near the Slate River, a tributary of Lake Gogebic about a mile outside of Enbridge’s adopted stretch (I don’t know why they couldn’t afford three miles!), Line 5 spilled another 285,000 gallons.

That’s more than half a million gallons of oil in one very short stretch of pipeline. And the picture gets worse if you expand the frame only slightly: a spill into Siemens Creek near Ironwood in 1967, a spill just across the Michigan border near Kimball, Wisconsin in 1972, a spill not far from Watersmeet in 1979, a spill near Wakefield in 1992, a spill just north of Marenisco in 2015. That’s ten spills along just a 60-mile stretch of the line.

What’s to account for this cluster? It’s hard to know precisely—Enbridge isn’t telling. But we do know that pipeline construction crews in 1953 found the Upper Peninsula an extraordinarily challenging place to work. Large stretches of land in the National Forest are muskeg—soggy, swamp-like blankets of decaying vegetation that can swallow construction equipment whole. Confounded by these bogs, pipeline crews at one point resorted to the reckless measure of cutting holes in the pipe and filling it with water to get it to sink. The compromised line blew wide open when it was tested. One wonders what other short-cut measures must have been taken during construction. At what point—and where—might they reveal themselves?

Whatever the case, it can’t be a coincidence that Enbridge adopted its portion of highway at the very location where Line 5 has spilled so much oil. But either way, it’s also the case, typical for them, that this little act of “generosity,” even in a relatively obscure place, looks a lot like greenwashing. It covers over (but only barely!) the ugly truth about their pipeline and the damage it has already done— not just the damage it could do in the future.

Jeffrey, this is a beautifully written piece with critical facts that you have assembled. Thank-you so much...there certainly is a lot to criticize about Line 5...every inch really. The whole project is a relic of a diseased oil based economy. But, your specific geographically specific stories of spills and mishaps, one followed by another, are so important to make visible. Then, there are the hideous exploitations of tribal lands, with Bad River being an unfortunate focal point. In solidarity, Josh Mark, Chicago (formerly of Bayfied County WI).

Here’s a link to Enbridge’s environmental violations over the last 25 years. 103 violations resulting in over $280,000,000 in fines and penalties. That averages one environmental violation every three months for 25 years. Close Line 5.. we can move a pipeline. We can’t move the Great Lakes.

https://violationtracker.goodjobsfirst.org/parent/enbridge